Recently economic news has dominated the popular media. We’ve talked in depth about inflation, and provided resources to help you learn more about it. Now talk has turned darkly to rumors of a recession. While this is a critical economic topic that everyone should understand, the media does a pretty poor job of educating the public on what a recession actually is, how we know we are in one, and what that might mean for ordinary people.

Key Takeaways for this post:

- Recession is a political concept, not just an economic one

- Recessions occur when an economy produces less over a sustained period

- Inflation can be good for net exporter nations, and bad for net importers

- Income inequality makes recessions more dangerous

- There is no “magic bullet” to fight recessions. Every recession is different, and the solutions will be dependent on the conditions.

- Governments have some tools for fighting recession, such as raising taxes

- Fighting a recession and inflation at the same time is very problematic

What is a Recession?

Despite the many and varied definitions you will find confidently stated on social media and in the news, the exact definition of a recession is not agreed upon by economists or policy experts.

Some of the definitions commonly given for recession are:

- Whenever the GNP (Gross National Product) or GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of a country gets smaller

- Whenever economic growth slows down

- Whenever the economy measurably shrinks

There are problems with each of these definitions for many reasons. Most importantly, the way that economic trends are measured is, by itself, arbitrary and susceptible to the influence of politics and media narratives about the economy.

Want to watch a brief summary of the definitions and origins of recessions around the world? Watch CNBC’s video “What is a recession? | CNBC Explains”.

Why Does a Recession Happen?

At the risk of being reductive, a recession happens to some degree simply because we believe it is happening. It is partially the result of a drop in the collective confidence of people, business, and governments in the future productivity of the economy.

At the heart of causes for a recession are unknowns. Changes that markets can see coming, but the effects of which aren’t completely understood. Big changes in the global economy mean big unknowns, and big unknowns mean big risks.

Big risks mean big disruptions, and since no one wants to be the last to react to a change, economies sometimes contract just because nobody is sure what’s about to happen. Companies don’t know where to invest. Consumers don’t know what to buy. Things slow down.

Can you be sure that money invested today in a specific investment will be safe? That depends on you knowing more or less what the future holds. If the future is uncertain, very often, markets become uncertain. So causes for global recession can mostly be found in the unknown: risks of climate change, war, technology disruptions, demographic change, or population rise and fall.

GDP, Inflation, and Trade

GNP and GDP are measures of the value of goods and services sold in an economy (or by the economy as a whole), but they are not, by themselves, reliable measurements of economic activity. This is because they do not actually measure the production of real goods, nor the provision of services, but rather the dollar amounts paid for goods and services over a given period of time.

This means, for example, that as prices rise on goods such as energy and food, GDP also grows as a result of this revaluation of the economy’s output. Government agencies such as the US Bureau of Economic Statistics do adjust GDP to account for inflation, but this does not change the fact that for consumers, prices are rising due to the inflation, which means that the total amount of goods and services a person can buy are both going down.

Adding to this, GDP must also account for the amount of goods and services that an economy imports. This amount is normally deducted from a country’s gross GDP. When inflation is rising locally, this causes changes in the type and amount of goods a country imports. If your national currency is decreasing in value, this should mean that you are able to import fewer goods for the same amount of money. However, you should also be able to export more goods, as consumers in other countries are better able to afford goods that are paid for in your country’s currency.

All this leads to different outcomes for different countries. Some countries, particularly those that have strong export economies, such as Taiwan, Germany, Vietnam, Mexico, and China, benefit from the devaluation of their own currencies by being able to better compete with each other to export goods to net-importer countries such as Japan, the United States, France, and others. This means that inflation in those producer countries, to a point, is advantageous because they can capture more of the global market for their manufactured goods.

On the other hand, countries that rely on imported goods will find that inflation reduces their ability to pay for imports, and because their manufacturing sectors are not as large, they are not able to take advantage of this inflation to improve their competitiveness on the global market.

Inflation: Winners and Losers

All this comes down to there being winners and losers in times of high inflation. Right now, countries that export more goods than they import are going to find that their economies continue to grow, whereas countries that import more goods will find themselves less able to buy things.

What this means in practice is that if you live in a region or a country where manufacturing provides most of the jobs, you will be better off than in a place where services provide more jobs. This is because regions where manufacturing provides jobs will benefit from the increased competitiveness of their manufacturing industries, and more money will flow into the local economy.

Countries such as Germany will find during times of global recession that there is increasing demand for their goods, and because more of their workers work in manufacturing, therefore more of the money that goes to pay for those goods ends up in the hands of local workers. Sure, the global economy may be getting weaker, but German workers will be employed and earning a good living. As long as their work is competitive on the international market, they are safe.

At the same time, countries such as the United States and Japan will find the opposite. As they are forced to pay higher prices for goods made in places like Germany and China, money will leave their local economies, leaving less for spending on local goods and services. This will mean that there will be less money left over in the local economy, and people will become effectively poorer than they were before. Unlike in Germany, there will not be plentiful jobs. There may be things to buy, but there may be less money to buy them with.

This can all be made worse by the need to take steps to control inflation. As we discussed before, high inflation is damaging by itself, but the cure is often painful. Governments typically try to control inflation by raising interest rates on prime borrowers. What this means is that the cost of borrowing increases, while the profits from investing in government bonds go up.

This makes it more likely that investors will buy government bonds for their high interest rates, and thus there will be less money in circulation and fewer people borrowing money. That, in theory, can “break” inflation by shocking the system into valuing the money in circulation more highly than it otherwise would.

But there are limits even to this. As prime interest rates go up, the government is essentially paying the already rich to hold on to their money. When there is less money circulating, there is also less money being borrowed. As less money is borrowed, fewer investments in upgrades and new equipment can be made, and this can in turn have the effect of lowering the supply of goods and services. If the supply of goods and services is going down, this can cause prices on goods to continue to rise, even though there are fewer people seeking to buy them.

So as you can tell, interest rate hikes are only effective up to a point, and that point may be reached very quickly before its effectiveness is lost.

Exporter Vs. Importer Nations

During the past 25 years, with historically rock-bottom inflation rates, countries like the United States, France and Britain experienced steady, but slow economic growth, as their ability to buy goods from abroad continued to increase, while local services became stronger, creating “value” which could be shared within local economies. But without the ability to import goods cheaply, this system will be threatened.

These conditions led to steadily increasing standards of living, even as these economies were producing fewer “commodity” goods such as oil, minerals, metals, and other things that the economy uses to produce goods. However, now that inflation has set in, these many years of increasing standards of living will be under threat. Increasing costs of fuel and basic necessities will mean that services (who have to pay their workers more to maintain their living standards) will in turn become even more expensive.

Because American and Western European standards of living are based on cheap imports to keep people comfortable and living at a high standard, the sudden and sustained increase in prices on the global market means that people in those countries will have less disposable income, and will spend more of their money on basic necessities.

Countries which have benefited from globalization with rising standards of living will thus find that their standard of living will be under threat. It may even decrease during a recession, while those countries which rely on exports to keep their economies working will find themselves in a much better position. Workers in importer nations will find that they have less bargaining power, and that their money doesn’t go as far as before. Workers in exporter nations will find that their bargaining power is increasing, and their pay will keep up with inflation.

Of course, even that trend has limits. Eventually, exporter nations will also find that importer nations, less able to buy their goods, will begin importing less. Increasingly, local manufacturing in those countries will become more competitive, and the global system will slowly readjust to account for less overall imports and exports. Thus even exporter nations are not completely safe from the impact of inflation and recession. They too will find that their growth has limits.

The Legacy of Inequality

There is another lurking problem in the global economy, and it is one that especially affects importer nations. It is the rapid growth in income inequality, and it will now rear its head at the worst possible moment.

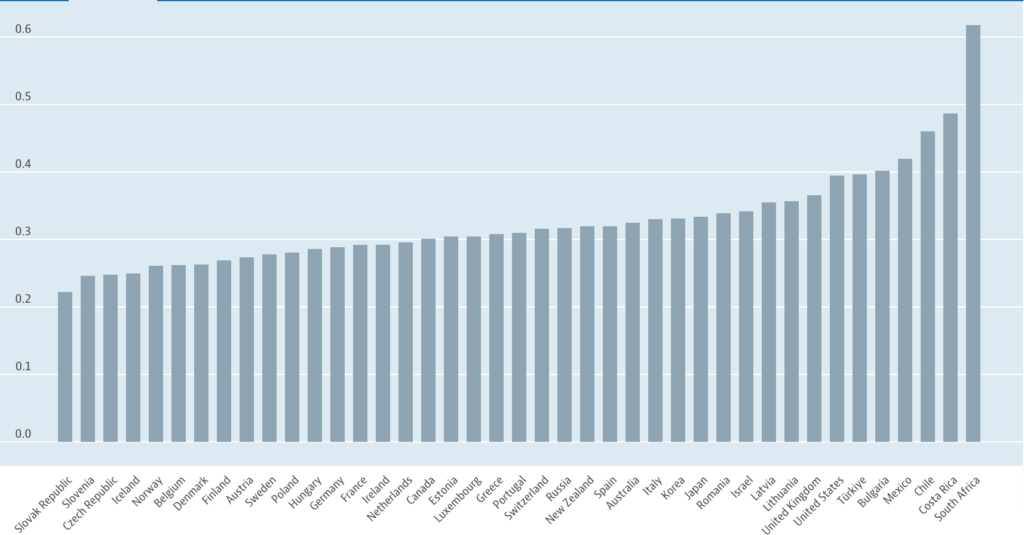

The above data from oecd.org shows inequality by country using the “Gini Coefficient”, which is a measure of cumulative inequality given as a value between 0 (perfect equality) and 1 (perfect inequality). As the chart shows, heavy importers such as the United Kingdom and United States have higher inequality, along with developing countries.

Over the past 50 years, while economies that relied on imports continued to grow, another thing that happened was that workers and consumers in importer nations slowly lost bargaining power. Because the cost of imported goods was becoming cheaper all the time, employers were able to squeeze workers by failing to raise their pay or provide competitive benefits over the course of many years. If workers quit or complained, their jobs could be sent overseas.

At the same time, profits for businesses have soared, as globalization has produced huge opportunities for the business sector to save money by exporting jobs to cheaper countries, and sell their services at a discount to increase their own market share. However, these trends have their limits. Today, American workers in particular are paid a tiny fraction of what business executives earn, and their share in the total wealth of the economy has plummeted to historic lows.

Today America in particular is experiencing higher levels of inequality than it has experienced in over a century. While standards of living are higher than they were the last time this level of inequality was seen, inequality is by its nature destructive to economic stability. If more money is in the hands of the very few, then there are fewer customers from any goods and services. More money goes to financial investments, and can be used for rent-seeking behaviors (such as buying real-estate) which in turn makes the economy less productive and less stable. A country where a handful of people have all the money is a country that is not able to adjust quickly to any crisis.

All of these factors combine to create a situation where workers are not able to take pay cuts to support businesses that are not growing. Workers have lost so much of their buying power, that businesses are finding it harder to survive with fewer customers able to pay for their goods and services. In essence: the bottom is falling out of the economies that have been experiencing growing inequality, as there are now fewer consumers with less disposable income to buy from local businesses.

Today, huge potential emergencies are developing in otherwise developed countries, where the ability of businesses to operate is being threatened by a working class that is unable to pay for basic necessities, such as housing, food, and fuel. If workers are unable to engage with the economy, this will worsen the situation, and cause businesses to fail. As businesses fail, jobs will disappear, and the situation will become even worse.

The Threats of Inequality

A recession is not dangerous simply because it means that an economy is shrinking. It is dangerous because as an economy shrinks, there is a risk that specific parts of that economy will completely cease to function.

For example, what happens when millions of people are suddenly unable to afford a place to stay? Well, in the United States, it’s estimated that there is a need for at least 3 million additional housing units in order to provide affordable housing to the most vulnerable workers. Workers however, do not have the money to pay for this new housing, and investors do not have an incentive to provide it. Quite the opposite in fact, as a shortage of housing means short-term profits for housing developers, who are selling or renting houses at inflated prices due to the shortage. This means big profits for investors, but at the expense of the economy as a whole. The more people pay in rent, the less they have for everything else.

However, it’s not hard to picture what happens when literally millions of people become homeless. Their ability to work, to buy things, or indeed to do anything but survive becomes seriously threatened. This can lead to mass unrest, and historically has been a cause of revolution and regime change. These may sound like overly dramatic characterizations, but it’s estimated that as many as half of American households do not have the financial means to endure job losses for even two weeks.

Inequality, the capturing of most of the benefits of globalization by an elite few in the business and political spheres, may be creating an enormous danger to the peace and wellbeing of millions of people worldwide. If governments are not prepared or willing to address these problems head on, a recession could turn into something far, far worse.

How to Know We’re in a Recession

As we’ve noted, there is no formula for defining what a recession is. Rather, governments decide to call a period of economic decline a recession if and when it becomes necessary to acknowledge that the fundamental drivers of economic growth are not functioning, or are unable to sustain the population at the same standard of living as before.

The main justification for calling something a recession is that governments must come up with a policy response to the situation. It’s a bit like “declaring an emergency.” A recession is a time in which governments and businesses all acknowledge that yes, the economy is not functioning the way we want it to, and that therefore there must be changes adopted, in order to avoid the worst possible outcomes.

So we should view this debate about what a recession is and what we should do about it as more like a debate about whether governments need to step in and take a more active role in the economy. Viewed from this perspective, the question of whether we are in a recession is really more a question of whether we think we need help from the government or not.

If you’d like to learn more about whether we’re sliding into a recession or are already experiencing one, we recommend the podcast episode “Are We in a Recession? It’s Complicated.” by the Wall Street Journal from July 2022.

Government Responses in a Recession

Given that we’ve established that the important question is really whether we decide we are in a recession or not, the question then becomes: if we are in a recession, what do we do about it?

Not all Recessions are Created Equal

It’s important to note that just because the economy is shrinking, does not necessarily mean that we need to do anything about it. Not all recessions are the same. For example, historically the ends of wars have triggered economic recessions. This makes some sense, as demobilization of war efforts do put millions of people temporarily out of work, as economies reorient towards a peacetime footing. The need for wartime production is obviously over at the end of a war, so demobilization can produce “recession” conditions. However if the economy is otherwise healthy, these conditions won’t last long.

This makes some intuitive sense. At the end of WWII, for example, many millions of soldiers around the world returned home and resumed their old occupations. Many more, having been trained by the military to do new jobs, were able to start businesses or enter new professions for the first time. This sudden influx of skilled workers temporarily meant that unemployment was high, yet there was also a huge opportunity for businesses to reorient towards a new professional economy with many more skilled workers. Therefore the end of WWII meant the beginning of a sustained period of economic growth all over the world. Recession in that scenario was simply the necessary period of adjustment.

Historically, while recessions do follow events like wars, there are powerful economic forces that quickly improve conditions for most people. The end of a war means many people returning to work, and it usually means better access to food, fuel, and other products of industry that were rationed during wartime. Thus the post-war economic booms of the 1920s and the 1940s-50s were natural results of a return to peace and the economic benefits of ending wars.

However, if a recession is more based on long term economic conditions that are unlikely to correct themselves, then government intervention becomes more likely, and possibly more necessary.

So what kinds of changes are we talking about?

- Taxation

One of the key tools for governments to control economies is through taxation. Like interest rates, tax rate hikes can have the effect of changing the amount of money circulating in the economy, as well as how that money is being spent.

As an example, raising taxes on capital gains (the tax on the value of investments you own) can cause investors to reallocate their funds to investments that are more focused on long-term growth over short term gain.

So, in a hypothetical scenario, if I am an investor and capital gains taxes go up by 10%, realizing profits on my investments becomes more expensive. This may cause me to invest in things that I believe will not grow as fast, but will be safer long term investments. With higher taxes, my reward for taking risks with investing is reduced. I have more of an incentive to seek safer, less profitable investments.

Also, I may choose not to realize all of my gains by selling my investments, but instead defer those capital gains taxes by either reinvesting, or taking a loss by “writing down” unsuccessful investments I have made in the past (a tax procedure whereby I declare a loss of my investment). This can have the effect of causing companies and investments that are not performing up to previous expectations to shut down, or vastly reduce their market value, making them more affordable to smaller retail investors.

By taxing the super rich or big businesses, the government is also able to exercise some control over the prices of investments, and by extension, the prices of goods and services. If taxes on investors go up, this can cause them to sell investments, or to have less money to invest. Over time, that lower demand for investments lowers overall prices, and improves the “Price to Earnings” or “P/E Ratio” of public companies.

Finally, the last way that taxation can improve the situation is by transferring some wealth from the super rich to ordinary citizens through transfer payments, commonly programs like Social Security, welfare, universal medicine, education, and other government spending. By taking wealth from the super rich and investing that money in the working and middle class, the government can very effectively mitigate the consequences of a recession by propping up the buying power of consumers using the money taken from the super rich.

Changes in tax policy, though they remain controversial, are really the government’s most powerful tool for fighting recessions and economic instability. If a recession gets bad enough, aggressive new tax policies become more and more likely.

- Debt Spending

While raising taxes and increasing government spending and transfer payments is one way of fighting the recessionary cycle, another way is through debt spending.

In a situation where overall demand for goods and services is dropping, the government can lower interest rates to increase overall borrowing, which can improve economic growth by making more money available to invest in long term projects. However, with inflation at an historical high, this approach is unlikely to work, and will most likely not be popular, as any increase in debt will drive further inflation and reduce buying power even further.

There have been situations in the past where debt spending through a recession failed to work, and produced what we now term “stagflation,” or the stagnation of wages combined with inflation in prices. This happened in the United States and to a lesser extent in Europe during the 1970s, when governments tried to kickstart economies by borrowing and spending more money, which only caused inflation to continue to rise (as competition for limited resources was high) while wages continued to stagnate.

That happened because the recessions of the 1970s were caused by a drop in the supply of energy, particularly of oil. With less oil to spare, government spending only helped to drive the price of oil even higher. In that scenario, government spending could not end the recession because the recession was “structural” in nature. It needed to be solved by changes in technology and industry, not through financial means.

Still, in the right conditions, debt spending can provide an engine for economic growth. It can be argued that debt spending was largely how countries like the United States and Japan have avoided recessions for decades already, but the key difference today is that inflation has gotten out of control.

With inflation high, debt spending, or an increase in money creation and government spending is unlikely to make the situation better for ordinary people. Instead it’s more likely to make the already rich, even richer, and to make life only more expensive for everyone else.

- Austerity

Finally we arrive at the other extreme of possible government responses to recession: austerity.

Austerity, to avoid an extremely technical discussion, is essentially the theory that you can improve the performance of the economy by reducing government debts and current account deficits. Advocates of the theory argue that government spending “crowds out” private industry and creates conditions in which private business cannot compete with the government.

There are scenarios (such as the one mentioned above) where this has been true. However the effectiveness of any government policy is always, always dependent on the unique conditions that are causing recession to begin with. No solution ever works for all scenarios.

So, to give a more concrete example: if the government is paying NASA $50 Billion a year to develop rockets for its space programs, this makes it much more expensive for private companies such as SpaceX or Blue Origin to do the same thing, since NASA is competing for resources including talent, fuel, components, and even real estate. By reducing government spending, you allow private industry to pick up the slack and find more efficient ways to do the same things.

As we noted in our resources post on inflation, political economists like Steve Keen and Mark Blythe have argued vehemently that austerity policies mostly serve to transfer the debts of governments onto the working poor. By reducing spending in the face of high government debts, governments unintentionally put a higher burden on working class people, who are suddenly faced with fewer available services, resources, and jobs.

Steve Keen points out that if governments want to run budget surpluses, this means that they must constantly bring more money in than they have spent. That money ultimately comes out of the economy, and what that means, long term, is that businesses and individuals must borrow more in order to allow the economy to grow; otherwise the economy will shrink with less money flowing into it than flows out. During an economic downturn, less money is being spent or borrowed, which means that austerity should cause private debt to rise unchecked, while the economy fails to grow.

It’s a bit like believing that because an overweight person would benefit from losing weight, therefore any person would benefit from losing weight. Yet if a person is underweight, then losing weight will only harm them. Austerity for the sake of austerity is dangerous, because it ignores what is causing the problem: it demands that an economy that is “skinny” lose even more weight to be healthy. Austerity can work in situations where inflation is rising because of a lack of available resources, but that is not really what is driving most inflation today.

Want to know more about the effects of austerity? Watch this interview with Steve Keen and learn why he calls Austerity “naive”.

In addition, waves of privatization that seek to apply budget discipline and austerity typically benefit private investors and the super rich, as they are able to assume control of the profitable aspects of some government programs, while essentially disposing of those aspects that cannot financially sustain themselves. This puts even more burden on the working class, who find themselves again with fewer jobs, and with access to fewer services, less education, and less government help than before.

Advocates of austerity argue that these short term difficulties produce a leaner, more competitive economy that is better able to compete in the global marketplace long term. But as Blythe notes: reducing your own debts and suffering from short term losses may work if it makes your economy more competitive for the long term, it doesn’t work if everyone else is doing it at the same time.

Imagine living in a town where everyone is in debt. If you reduce your own debts by not buying anything unnecessary, you can get yourself out of debt in time. But if everyone tries to save money at the same time, you won’t ever be able to get out of debt, because nobody else will be spending money. No salaries would be paid. No goods would be purchased. If everyone does austerity, nothing gets done.

If you want to learn more about the history of austerity and its effects on today’s economy and society, we highly recommend Mark Blythe’s bestseller “Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea”.

For all of these reasons, despite many years of efforts to promote austerity as a solution to economic problems, most notably in places like Ireland, Greece, Spain, and the United Kingdom, there is less and less political will to engage in austerity policies today. The push for developing nations to adopt austerity to become more competitive has largely run its course, with many nations realizing that these policies don’t work when everyone is doing them.

BudgetBakers is a private company with no active investments in any of the industries or activities described here. This is not financial advice. Customers should seek advice from licensed financial advisors before making any investment or financial decisions.